By: Ahmed Eladawy, Saker El Nour, and Yasmine Hafez *

Even when climate change is not the raison d’être of conflict, it may increase and expand the prerequisite conditions of violence. Hence, environmental research in Arab work is rooted in the understanding of intertwined connections between socio-economic poverty, environmental vulnerability, and violence [3]. This requires bridging the gap between knowledge production and considering the security dimension, communities’ concerns, and ethical dilemmas. This causes environmental vulnerability to expand from the everyday experiences of violence, poverty, and exploitation to a broader fragility of the Arab world as a part of a web of capitalist exploitation, imperialist interests, and domestic hierarchies.

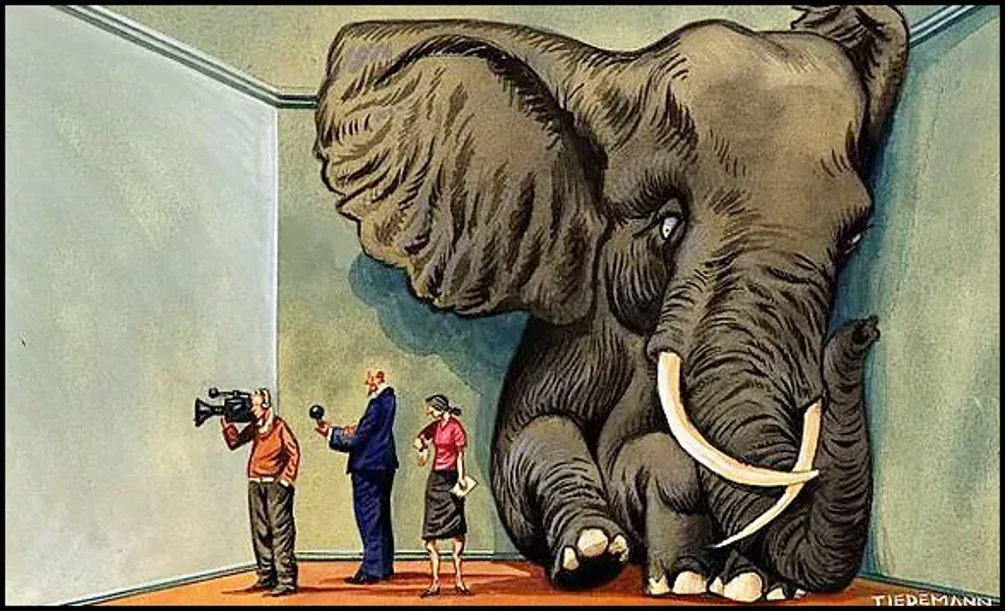

Climate change is frequently perceived as less immediate in the Arab region, where it often receives limited attention in public discourse and media coverage, often being viewed as an external issue [1]. As such, Climate change had been discussed with a “Western Gaze” that reflected a continuation of orientalizing the region [2]. However, the Arab region is a mosaic of countries dealing differently with their energy resources and having various levels of resilience and vulnerability to climate change impacts. While acknowledging the role of colonization and occupation in resource depletion, this article highlights the serious barriers facing researchers working on environmental studies and climate change issues in the Arab World.

The various levels of positionalities between diverse local and international actors complicate the work of Arab researchers. On a state level, it is challenging to work in “depoliticized spheres” while maneuvering national security grips and fighting greenwashing attempts and politicized environmental agendas. It is also difficult to effectively communicate with local communities on the ground and explain how our work does not prioritize environmental discourse over their survival needs and livelihoods.

At the core of the Arab region, a silent struggle unfolds far from the headlines—a battle not just against the rising tides of climate change but also against the invisible barriers that hinder studying and analyzing climate change itself [4]. Researchers and journalists, armed with their determination and expertise, navigate a labyrinth of challenges as they seek to shed light on the environmental crises and climate change impacts on local communities in the region.

First, funding, an essential resource, is often geared toward climate change mitigation efforts [5], leaving adaptation strategies gasping for breath. There are agendas and directions that often come with the funding that hinder the independent and critical nature of the pursuit of knowledge by determining knowledge orientation and the volume of knowledge production. These directions are often narrated by Western interests, giving weight to the well-being of some at the expense of the majority.

Second, even when succeeding in working “independently”, the most formidable foe lies in the shadows: the restricted exchange of crucial environmental data and information. This bottleneck stifles not just innovation but the very foundation of climate crisis research. The quest for accurate studies, reliant on the gold standard of comprehensive fieldwork and unfettered access to government data, becomes an exhausting task [6]. As such, echoing through the corridors of universities and media houses are tales of frustration.

Voices from the water sector speak of a Sisyphean task—chasing after updated, transparent data on groundwater sustainability, water quality, and the operations of mega control structures. The elusive nature of national water-sharing policies, water distribution, and access adds layers to an already complex puzzle. Added to this is the restricted deployment of field research devices, such as drones, to study and analyze diverse ecosystems—from the bustling life beneath the seas to the serene flows of rivers and lakes. These restrictions limit access to data and form invisible walls around knowledge production that are often hard to bypass.

Among the most guarded data are the details of national development plans and the environmental impact assessments of megaprojects. Here, the struggle is not just for access but for transparency, for the right to scrutinize the decisions shaping the future of nations. This is banned by the fear that real data, if misrepresented, could incite public panic, especially concerning sensitive issues like water and air quality. This anti-effectiveness patriarchal approach backfires, exacerbating public distrust in national research institutions and creating a vacuum where misinformation can thrive. Enforcing data security measures ranges from explicit ‘Don’t share data’ mandates to more sophisticated strategies of securitizing scientific research and favoring research centers affiliated with ministries over more independent academic institutions. This not only skews the landscape of scientific research but also mires data quality in the quagmire of inefficiency, with each entity left to devise its data management practices in the absence of uniform policies.

We also note the stratifications between local and international experts, where “consultants” or “experts” are often preferred based on their nationality and international privilege. Access to data for international experts often steps in to fill the void left by restricted access. This leads to a proliferation of studies that, in the absence of a comprehensive local context and accurate data analysis, may lean towards more extreme or skewed interpretations of the Arab world. Such a landscape paves the way for biased analyses to become the norm rather than the exception.

This fragmented approach not only impedes the integrity of research but also stymies governmental planning and project execution, leaving officials scrambling for the standardized data essential for informed decision-making. The result is a landscape where the quest for knowledge is not just a challenge but a reflection of the broader struggles for transparency, trust, and truth in the Arab region’s battle against climate change impacts and environmental crises.

Addressing environmental issues in the Arab region requires a nuanced understanding that goes beyond oversimplified narratives, and supporting scientific research in this field is critical. Yet the region faces challenges in fostering robust local dialogues and policies aimed at tackling the climate crisis effectively due to the limited scope of scientific debates and a tendency for academic discussions to align with official positions without adequately exploring alternative viewpoints or indigenous solutions.

The development of climate change policies in the Arab world often reflects complex interactions with global impacts; however, there’s a pressing need for these policies to be rooted more deeply in local contexts and based on scientific evidence. The emphasis on solar energy, for instance, shows an effort towards sustainable development, though most of it is exported to Europe rather than local transition to clean energy. This, in addition to coinciding with continued investments in fossil fuel industries [7], highlights the tensions within the region’s approach to energy transition.

This situation illustrates the broader challenge: bridging the gap between the adoption of international models and the creation of strategies that are both scientifically sound and culturally resonant. The Arab region, with its rich diversity and unique environmental contexts, has the potential to lead with innovative climate solutions that are tailored to its specific needs and realities [8]. Moving forward requires fostering open and equal scientific dialogue, supporting research, and developing policies that genuinely reflect the aspirations and concerns of its people, ensuring a sustainable and resilient future for all.

As we stand on the precipice of environmental upheaval, the path forward for the Arab region is clear: embrace a just transition that addresses the core challenges of data accessibility, the lack of vibrant scientific and public engagement, and the critical need to move beyond the mere replication of Western climate strategies. The cornerstone of this transformative journey should be the launch of a Regional Data Sharing Initiative, bolstered by international support of an era of transparency and cooperation.

But change doesn’t stop at data democratization; it also requires creating public spaces where voices from across the spectrum—local and international scientists, policy influencers, activists, and grassroots leaders—converge in dynamic forums to wrestle with the pressing climate issues. These discussions will not only illuminate the multifaceted challenges at hand but will also spark innovative solutions based on collective work and local organization. By integrating local expertise and knowledge into the heart of policymaking, the Arab region can ensure its policies are not just replicas of ill-fitting models from the Global North but are instead reflective of the rich tapestry of local needs, scientific insights, and community aspirations.

In redefining the narrative within the Arab region, there exists a critical opportunity for active contribution to the global climate change efforts, emphasizing a methodology that is both inclusive and equitable, deeply ingrained in the region’s varied community landscapes. This endeavor, while challenging, is brightened by the prospect of a future where environmental sustainability and social justice are seamlessly integrated, propelling the region toward a just transition. The current landscape underscores the vital importance of solidarity and cooperation among environmental researchers, promoting mutual support to overcome obstacles related to data accessibility and research securitization and ensuring the integrity of environmental discourse against the risks of greenwashing and politicization, especially under international pressure.

The increasing incidents of climate-related violence and their marked effects in the Arab world accentuate the necessity for an Arab collective approach focusing on data sharing, sincere research, and the eschewing of simplistic narratives for a fully informed and calculated climate change strategy.

References

[1] Eskjær, M. F. (2017). Climate change communication in Middle East and Arab countries. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science.

[2] Hamouchene, H. (2023). Dismantling Green Colonialism: Energy and Climate Justice in the Arab Region. Pluto Press.

[3] Thomas, E. (2024). Land, livestock and Darfur’s ‘Culture Wars’. MER issue 310 “The Struggle for Sudan”. Retrieved from, https://merip.org/2024/04/land-livestock-and-darfurs-culture-wars/

[4] Watson, C., & Schalatek, L. (2020). Climate Finance Regional Briefing: Middle East and North Africa. Climate Finance Fundamentals, (9).

[5] El-Adawy A., & El Nour S. (2022, August 1). Before COP: On the importance of adaptation in Africa. Mada Masr. Retrieved from https://is.gd/b2hZiY

[6] Bakr, A. (2022, March 9). IPCC experts say climate research funding for Egypt, Africa insufficient to adapt to threats of climate change. Retrieved from https://is.gd/1k9Ub8

[7] Wehrey, F., Dargin, J., Mehdi, Z., et al. (2023). Climate Change and Vulnerability in the Middle East.

[8] El Adawy, A. (2023). The Arab Gulf and Climate Change: Massive Steps or Greening Non-negotiable Fossil Fuel Revenues.

*The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the views of our employer or the publication platform.

0 Comment

Leave a Reply