By Ahmed El-Adawy & Saker El Nour August 1, 2022, Mada Masr

Over the past few months, there have been many discussions on climate change issues in light of the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) on impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. In a world that is becoming increasingly panicked about the impending climate catastrophe, the agendas of developing nations have diverged from those of the developed world. While growth in poor countries depends on their ability to adapt to the effects of climate change, developed nations want to simply forget the past and share the burden of “mitigating” this reality shaped by their murderous policies by reducing the use of fossil fuels.

Populations across the African continent continue to feel the effects of low development rates, at a time when the Global North is only expected to make slight changes that continue to accommodate privileged lifestyles — a phenomenon described by German researchers Ulrich Brand and Markus Wissen in their important book, The Imperial Mode of Living. Everyday Life and the Ecological Crisis of Capitalism.

***

In this text, we try to move away from the dominant narratives that focus on emissions reduction without taking into account local development and the provision of basic services to people, as well as the measures needed to adapt to the harsh effects of climate change on the local social and ecological systems in Egypt and Africa at large.

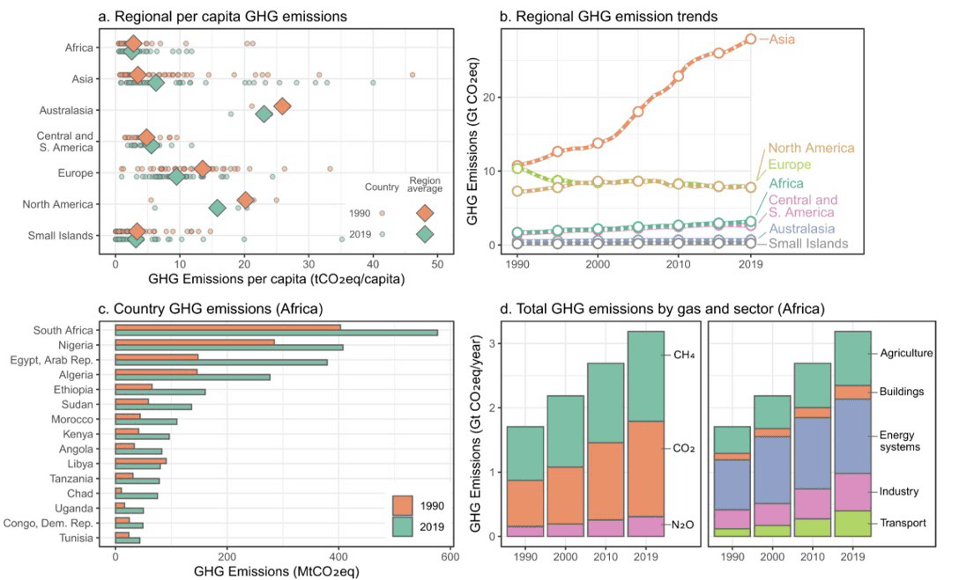

Looking at climate change indicators in Egypt, we find that we are among the countries that have most seriously worked to reduce emissions, on par with European countries. Despite Egypt’s emissions ranking the third highest in Africa between 1990 and 2019, behind South Africa and Nigeria, our contributions (excluding emissions created during the production of imported goods), remain limited compared to global carbon emissions. Egypt’s average annual per capita emission is 2.32 tons, less than half the global average. On the regional level, Qatar’s per capita emissions are 16 times those of Egypt, while Saudi Arabia’s are seven times higher. At the global level, China’s per capita emissions are three times those of Egypt, the United States’ are six times more, and Germany’s are four times higher.

Egypt continues to rank well as far as the goals set in the 2015 Paris Agreement, placing 21st out of 60 countries on Germanwatch’s Climate Change Performance Index, one of the fairer and more comprehensive indices of its kind. Meanwhile, the US, Saudi Arabia and Australia remain at the bottom of the list.

Based on this data, the nomination of Egypt to host the 2022 UN Climate Change Conference (COP27) seems reasonable. Perhaps the countries of the Global North decided to reward Egypt for its experience as a “developing” country that fared relatively well in fulfilling its commitments to the Nationally Determined Contributions. Egypt’s progress, according to these metrics, can be attributed to its expansion in the use of natural gas, as well as its commitment to ambitious plans to make renewable energy account for 42 percent of its energy mix by 2030. This progress is supported by the expansion in solar energy projects such as the Benban project in the Aswan desert and comes despite the parallel expansion in the construction of low-density desert cities that have a higher water and carbon footprint than the older cities.

Here, it’s important to point out the conflict of interest between the ambitions of international financing institutions on one hand and the state on the other — which should be committed to its residents’ quality of life. In Egypt, this conflict is apparent in the institutional framing of national road projects as a supposedly sustainable means of lowering emissions.

This contradiction is also seen in the government’s prioritization of nominally pro-environment projects: Why do financing institutions and the state, who show great enthusiasm for green hydrogen or electric vehicle projects, lose this excitement when the discussion turns to providing low-cost maintenance for mass transit to decrease pollution in our crowded cities? Where does this excitement go when we speak of replacing tuk tuks with more environmentally friendly alternatives, as India did, or of significantly expanding mass transit projects such as electric buses and trains in the old cities?

There are two reasons for this disinclination. First, there is the hegemonic neoliberal economic system that supports private sector expansion rather than public investments in transportation, from which states around the world have withdrawn. Second, these projects are aimed at preserving the current international division of labor: the Global South produces green hydrogen, which is then exported to the Global North at cheap prices; and electric vehicles manufactured in the north are imported by the south at high prices. These projects also help preserve the imperialist mode of life in the north, with a generous contribution from us who are at risk of bigger problems and need to put more effort into adaptation.

Egypt’s success in emissions reduction is unfortunately contrasted by the negligence of the more important areas of adaptation — seen not only on the level of projects but also in the limited funding for research. This negligence means Egypt has not fared as well in adaptation metrics in comparison to other African countries such as Kenya, which has relatively better research institutions.

Here, we ask whether international interest and glorification of Egypt’s experience with climate change adaptation is rooted in its alignment with a dominant Western agenda that prioritizes emission reduction rather than centering each population’s needs when it comes to adapting to climate change.

***

Climate change primarily leads to a gradual increase in global temperatures, causing a rise in sea levels as ice melts, a decline in crops, agricultural production and biodiversity, the increased precarity of life in coastal areas, the possible destruction of coastal inhabitants’ means of living and the generally disastrous consequences for quality of life in general. We are not only talking about the complete submersion of some areas, which could be escaped through migration (assuming it is allowed), but also the frequent recurrence of extreme and unfamiliar weather events such as heatwaves, floods, droughts and the outbreaks of diseases they can cause. These events have already begun to occur.

Heatwaves, which used to happen once every 50 years, will now, according to researchers, happen 39 times every 50 years. Droughts, which used to occur once every 10 years, are now predicted to happen four times every 10 years, according to the worst-case scenario. In short, this massive disturbance will affect all facets of life on the planet in daily and direct ways. The IPCC’s latest report presents the losses accrued by all countries between 1991 and 2010 due to climate change as a percentage of GDP per capita — Egypt’s was 12 percent.

This situation puts us before two paths that must be pursued simultaneously. The first is a path of mitigation or a way of slowing down climate change by reducing emissions that directly increase the planet’s temperature. The second path is one in which we adapt to expected changes, which entails being prepared for changes that are already happening and dealing with all possible effects on people’s means of living in the most vulnerable and endangered areas.

Mitigation is affected by many factors, chief among which is our ability to reduce emissions by the required levels while ensuring that ecosystems continue to absorb carbon with the same efficiency. Adaptation evokes questions regarding the regions and peoples who face the greatest existential risks of climate change, and the historical responsibility of the developed world — it could drive us, as developing nations, to ask for reparations, rather than loans and grants, for adaptation.

The future of Africa will not stop at growing hunger rates, poverty rates, migration and conflict, but could be even darker. By 2030, climate change could cause at least 250,000 more deaths annually due to Malaria, heat waves and malnutrition resulting from global drought. A study by Stanford University concluded that climate change contributes to organized violence and conflicts in Africa and other places in the world. For example, in Sudan, an indisputable link has been established between rainfall and conflict in Darfur, as outlined in the book Sudan: Wars of Resources and Identity by Mohamed Suleiman. The IPCC report says that even if we can bring down emissions, as long as the indicators of global inequality persist, negative consequences would remain inevitable and may even overwhelm our capacity to adapt.

How does the global order handle the problem?

Simply put, through its substantial grants, the global order pressures Africa to stop constructing power plants, including those fueled by natural gas, and to reduce its coal use. This push is not intended to improve quality of life for Africans but rather to lower carbon emissions globally, even if it means hindering development plans that depend on cheap energy and which green energy cannot fulfill so far.

It is important to consider that African countries need massive energy and resource increases in order to better their citizens’ quality of life. The biggest effort to reduce and eliminate carbon emissions should first be made by the Global North, which is responsible for the problem. This reduction should be substantial enough to allow the Global South to safely use energy and resources, allowing it to advance quality of life to the necessary minimum. This does not mean the rejection of new energy projects on the continent, but that they first be directed at the welfare of people as part of local development planning. Clearly put, mitigation and adaptation programs to counter climate change should be part of Africa’s development plans aimed at improving the quality of life of its peoples. They should not be a continuation of the unequal distribution of burdens and financial and environmental gains.

The global order is unconcerned that Africans live and die in misery, without producing more energy or industrializing in accordance with their needs.. Meanwhile, the continent looks to produce 100 to 130 gigawatts of surplus electricity by 2030. Were this to happen, the amount of extra emissions in all of Africa, home to 1.3 billion people, would not exceed those of Germany, even after the exceptional progress the latter made by increasing its clean energy output to 41 percent of its total output.

Ghana, for example, has 85 percent electricity coverage for its citizens. Clean energy (mostly hydroelectric energy built during the post-independence era as part of Nkrumah’s self-sufficiency policy) accounted for more than 50 percent in 2015, with the rest coming mostly from natural gas and other imported sources. Its president recently announced the beginning of the biggest hybrid hydroelectric and thermal energy project in West Africa. In addition to Ghana, Zambia, Kenya and Ethiopia also have clean energy at more than 50 percent, compared to just 20 percent in the US. Do these government investments in Africa lead to direct improvement in the living standard of Africans? Or is the transition to clean energy being used as political propaganda or for capitalist investments to export green energy to the Global North in the form of green imperialism?

In comparison, clean energy as a percentage of total energy consumption is about 12 percent in the US and China, 14 percent in the UK and 10 percent in Japan. It might seem naive to compare the percentages of clean energy between Africa and developed countries, given the differences in amounts of total energy, but it’s an important indicator to determine the limits of climate change effects on producing clean energy in Africa, compared to less dependent developed countries. It seems obvious that countries with the largest emissions should bear the most responsibility for mitigation. Yet, the gradual clean energy transition should “leave no one behind” as the UN Sustainable Development Goals motto says. This does not mean that African countries should abandon a green shift but that they should take into consideration the massive global disparity in emissions and structure their green shift around their needs and the welfare of their people, not in support of the Global North.

The truth is that developed countries are not only responsible for what happened in the past, but also for pushing the planet toward new, real humanitarian crises in the near future through their denial of African countries’ right to develop. Most forms of support and facilitated lending provided by the Global North go toward projects that serve their own purposes, namely emission reduction and exporting clean energy. In tandem with this negligence of adaptation and local development needs, forests will continue to be destroyed (80 percent of available wood in Africa is used for heating or cooking purposes), and migration will continue to be a last resort for Africans, not due to a lack of development capacity but because of the repercussions of climate change.

***

In short, the evidence and the results of international climate summits indicate that the global order, and more specifically, the Global North, will not fund enough climate change mitigation projects that could practically help developing countries’ populations deal with the twin crises of climate change and hindered development. The global order, instead, wants to focus on mitigation even without enough support to preserve natural systems in Africa.

Egypt is spearheading a plan to split the $100 billion of annual funding provided by developed countries to the developing world 50-50 between mitigation and adaptation methods. On the other hand, the developed countries want an 80–20 split, where the lion’s share goes to mitigation and just 20 percent goes to adaptation. Neither of these options seems adequate given that the estimated total annual cost of adaptation for developing countries could reach $300 billion in the next 10 years.

Will African politicians give into this logic or will they learn from India’s experience in being able to clearly articulate its interests? India insisted on gradual mitigation policies rather than a complete stop to using coal in its energy mix, given the expenses. Will developed countries, as suggested in the research published in the sobering periodical ONE EARTH, use their massive capabilities to achieve bigger national goals than previously set, not only as reparations to Earth for their undeniable catastrophic contributions, but also to allow developing countries to continue economic growth?

Is it possible to reach a fairer and more logical solution? That would be a reality in which every country would adhere to its “fair” share of “accumulative and historical” emissions, where we preserve humanity’s goal of carbon neutrality by 2050, and only reach a 1.5 degree Celsius increase in global temperature, to be reduced to 1.2 degrees by the end of the century. If we follow this fairer approach, India, for example, should have the space to operate as it currently does until 2040, and African countries should not be required to invest their natural resources into mitigation, as that would not result in any tangible local environmental changes until 2040.

Kenya still might not fill its emissions quota as per the ambitious goal of global carbon neutrality, even if it continues to use coal as usual. As Leeds University researcher Andrew Fanning, who has calculated the total emissions of all countries, tells us, “The data says that China and the developed countries must work faster than expected and pay reparations, not grants or loans, much bigger than previously set, most of them for adaptation not for mitigation and should handle entirely the cost of mitigation strategies since they are the biggest source of emissions.”

It is neither fair nor logical to bet on African countries, including Egypt, to solve the climate crisis on their own and succeed where all developed countries have failed: to achieve citizens’ basic needs without overburdening the environment. Western researchers have spoken about the effect of green policies on the welfare of developed countries’ populations, but have the dangers of hindering basic services to Africans on the basis that they must reduce their carbon footprint been considered?

0 Comment

Leave a Reply